Canada's Car Stories

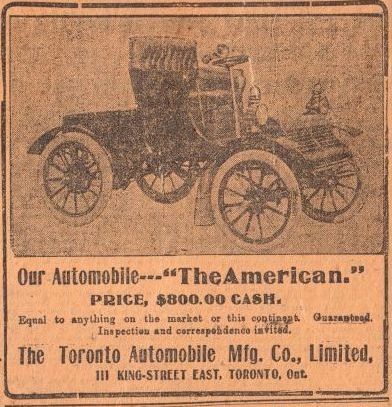

Toronto Automobile Co. advertisement, Toronto World, June 11, 1904. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

The Canadian Automobile Era

Canada’s automotive story began with little fanfare at the turn of the 20th century. Yet very quickly – over the course of just two decades – the automobile emerged as a major mass- produced and reliable form of transportation across the Dominion. From the first public demonstrations in the 1890s to the more than 33 million motorized vehicles on the road in 2016, the automobile became an integral part of Canadian society.

The automotive era began in a period of unprecedented technological innovation in modes of transportation. The 19th-century world moved goods and people by means of horse-drawn carriages, wagons, and coaches along with steam trains and ocean liners. As internal-combustion engines became more powerful, reliable, and affordable, carriage companies and other entrepreneurs began experimenting with gasoline-powered personal vehicles. Preferential trade agreements in the British Empire and close relationships with suppliers in the United States allowed Canada to become one of the world’s top automotive producers – at least until the disappearance of independent domestic car companies in the 1930s.

The car influences how Canadians interact with each other and their environment. From building and repairing, to driving and displaying, automotive experiences tell the story of modern life. These car stories reflect the social, geographic, and economic conditions that have shaped the nation.

Paved roadways were constructed to allow vehicles to travel with ease. Before this, however, cars would often get stuck or break down in the muddy, unpaved streets, like this one in Toronto in 1913. City of Toronto Archives, fonds 1244 item 42.

A “ferry” across Placentia Gut, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1938. The Rooms, VA 7-55.

Cover of Canadian Motorist, June 1927. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

“...every time a new car leaves the factory, it becomes unique and unlike any other car in the world. Each new owner takes it where he or she wants to go, often picking up scratches and dings along the way. Each owner gives the car a unique experience, adding another chapter to its ‘auto-biography.’”

Clara Dennis: Documenting Nova Scotia by Automobile

Clara Dennis

Clara Dennis at Purcell’s Cove, 1907. Clara Dennis Nova Scotia Archives, 1981-541 no. 1089.

Clara Dennis (1881–1958) was one of Nova Scotia’s first travel writers and also one of the first women to explore the province by car. Setting off in her automobile around 1930, she proceeded to capture several thousand images of scenery and everyday life with her camera. The automobile gave Dennis the freedom to explore all areas of the province, including the rarely travelled Cape Breton Highlands. She wrote three books about her travels of Nova Scotia and had articles published in a variety of magazines, including the popular Canadian Motorist.

Canadian Motorist, May 1929. Collection of Canadian Automotive Museum

“Then and there was born the resolution to seek and find Nova Scotia. I would travel over her highways and byways. I would know her cities, her towns, her villages. I would visit the remote and but little frequented islands of her coast. I would talk with the men, women, and children I would meet. In their lives would be unfolded the soul of Nova Scotia.”

“A mountain range has shut it off and while the world rushed on with the speed of the airplane, the automobile and the electric and steam railway car, the inhabitants of these villages pursued their leisurely way on foot, visited only on rare occasions by those who came by boat or braved the mountain trail on horseback or with dogs. But recently the Government began to build a road around the north of the island. Part of it was completed before last summer ended and we resolved to travel that road as far as it had been constructed.”

Road map of Nova Scotia, 1927. Rand McNally and Co. David Rumsey Map Collection, Cartography Associates.

1938 Hupmobile

Clara Dennis’s car, a 1938 Hupmobile. Clara Dennis Nova Scotia Archives, 1981-541 no.1330.

“Up, up, up wound the road, following the mountain trail. We passed through the village of Cap Rouge. This was the last sign of civilization. From then on the road got steeper and more winding. In two or three places we had to back the car to get around the curve, for the road had not as yet been completed. What a marvel to look back and down the road over which we had come, winding like a white ribbon up the mountain; the ships like toy boats riding at anchor in the sea below; the sense of height and depth around us.”

French Canadian Names

For auto manufacturers producing vehicles for the Canadian market – and especially during the 1950s and 1960s – French Canada proved a source of inspiration. Manufacturers of models destined for Canadian consumers gave the products French names to strengthen the cars’ Canadian cultural identity.

Acadian, 1963. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

The Meteor Montcalm was named after Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, the famous French general who defended Quebec against the British at the battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

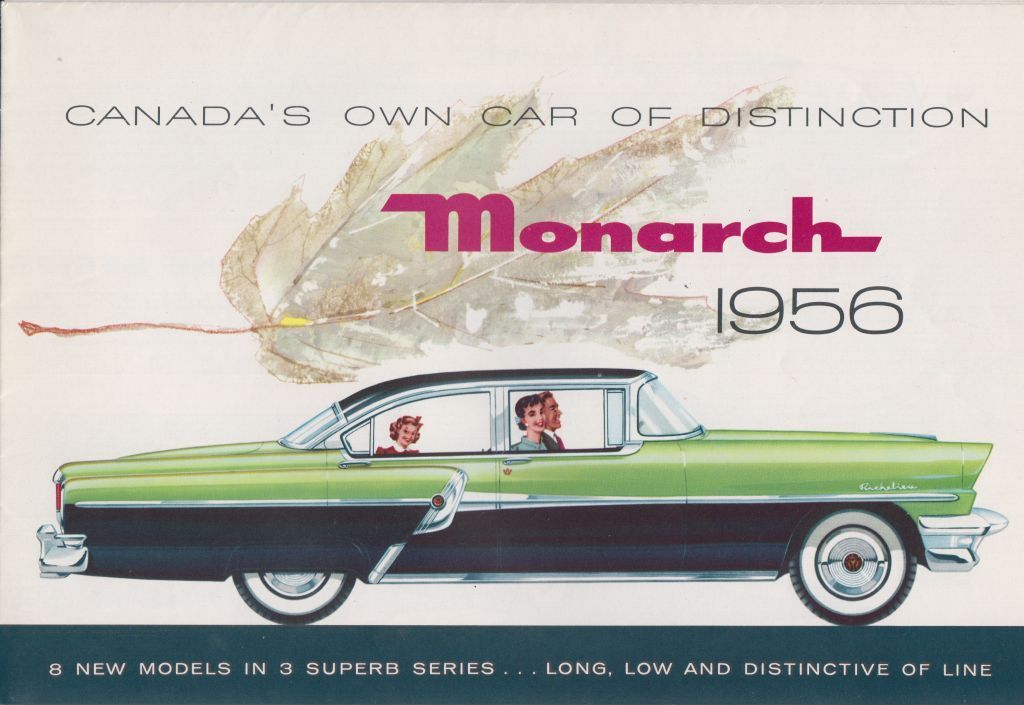

Between 1946 and 1961 the Monarch was a marque available only in Canada. The Monarch Richelieu got its name from Cardinal Richelieu, an adviser to King Louis XIV of France, and from the Richelieu River in Southern Quebec.

Between 1962 and 1971 General Motors of Canada produced and sold the Acadian. The marque’s name honours Acadia, a 17th-century colony of New France that included parts of Eastern Quebec and the Maritime Provinces. Acadians were deported from their lands by the British between 1755 and 1762. Many resettled in Louisiana, where the unique Cajun culture emerged. Years later some Acadians returned to the Maritimes after being granted permission by the British Crown. The majority settled in Eastern New Brunswick, where their culture and heritage remain today.

Promotional image of a Meteor Montcalm, 1961. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

The Ford Motor Company introduced the Frontenac as distinctively Canadian – naming it after Louis de Buade de Frontenac, a 17th-century Governor General of New France. The vehicle was produced and sold in Canada for only one year, with 9,536 assembled by the Ford plant in Oakville, Ontario.

Promotional image of a Monarch, 1956. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

Cadillac: A Canadian Connection

Antoine Laumet de La Mothe Cadillac (1658–1730) was a seigneur in the French colony of Acadia in the Maritimes. He went on to be commandant of Michilimackinac, at the junction of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, and later founded the city of Detroit, Michigan. In 1902 the newly founded Cadillac Motor Car Company in the United States took its name from the colonizer. Cadillac is an interesting character with a somewhat dubious reputation. Upon his arrival in New France in 1683, Cadillac invented a noble ancestry for himself, hiding his true identity as the son of a humble magistrate and a bourgeois housewife. He created his own family crest, which was later adopted as the car company’s logo. Cadillac was known as a boastful, ambitious, and quarrelsome man, who was often at odds with his colleagues in the French government. He was also the subject of gossip – rumours spread about him being chased out of France for his loathsome behaviour. When Cadillac returned to France in 1717, he was imprisoned in the Bastille for five months.

Cadillac logo, 1949. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

Selling Canadiana

Volkswagen Beetle

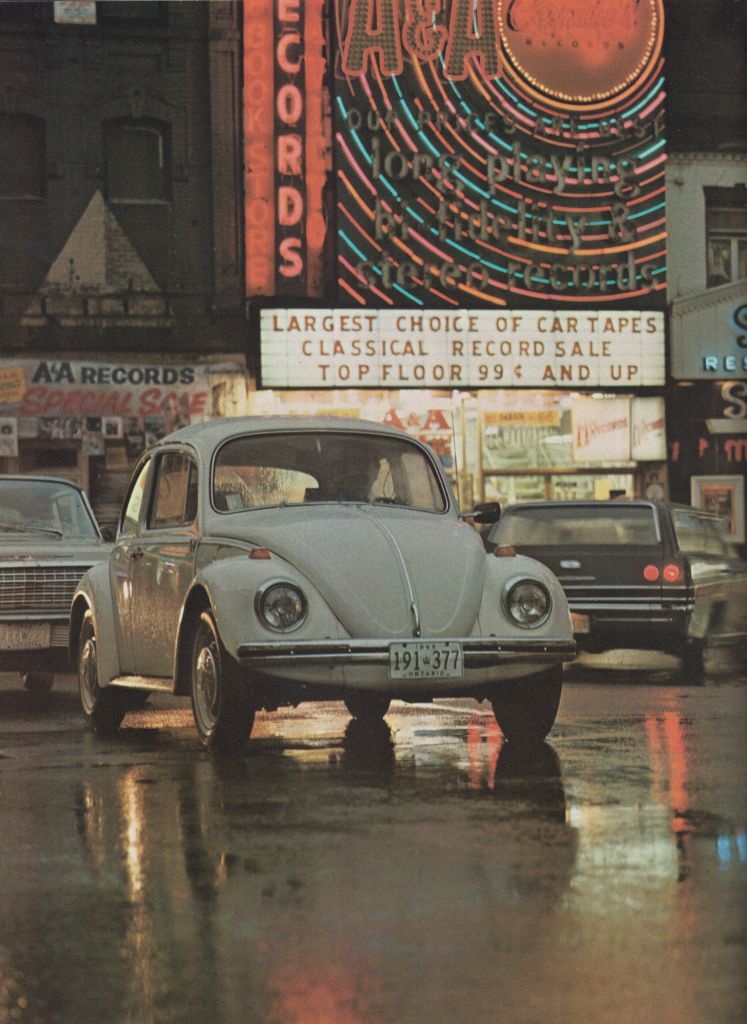

In 1960, the Volkswagen Beetle was Canada’s third best-selling car. A Volkswagen Beetle on busy Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario. Volkswagen Beetle brochure, 1969. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

After the Second World War and into the early 1960s, automobile manufacturers relied upon iconic Canadian landscapes and cultural references to promote automobiles to Canadian consumers. These advertisements featured an imagined Canada in which the car was integral to a life of hockey, family road trips, and outdoor winter adventures.

Many cars built and sold in Canada were modified versions of U.S. models altered specifically for the smaller Canadian market. Unique design features exclusive to these cars set them apart from their American counterparts, making them “Canadianized” vehicles. Later in the 20th century, as a greater number of foreign-built cars entered the market, advertisers continued to use Canadian imagery – from coastal villages to urban centres and mountain passes – to connect with customers.

Promotional image of a Meteor, 1959. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

In 1963 Volvo of Sweden set up its first overseas assembly plant in Dartmouth, N.S. The plant, which later moved to Halifax, produced the signature Volvo Canadian during the 1960s and early 1970s. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

Promotional image of a Meteor Niagara, 1959. Collection of the Canadian Automotive Museum.

Automotive Life

The widespread use of automobiles relies upon vast networks of infrastructure and laws that have been set in place over the years since the first vehicles hit the roads. Paved streets, service stations, and parking lots are just a few of the things that the automobile relies upon for its daily, year-round use. While automotive advertisements focus on the freedom of owning an automobile, urban traffic jams, snow storms, and speed limits are a daily reality for Canadians.

The growing population and workforce of the 1950s saw the rise of “suburban sprawl” – with new houses, schools, parks, and shopping malls and an increased reliance on the car. Plus other changes: in 1977 all posted speed limits across Canada were officially altered from miles per hour to kilometres per hour.

A Suburban District speed limit sign in North York, Ontario., c.1963. City of Toronto Archives, fonds 217, series 249, item 182.

For nearly half the year, driving in Canada faces the threat of snow and ice. Cleaning snow off a car in Ottawa, Ontario., 1959. Library and Archives Canada/Rosemary Gilliat Eaton fonds/e010977876.

Beverly Hills Motor Hotel in North York, Ont., c.1967. City of Toronto Archives fonds 217, series 249, file 8.

Coffee and donuts are constant features of Canada’s car culture thanks to the Tim Hortons chain, founded in 1964 in Hamilton, Ont.The first Tim Hortons restaurant, Hamilton, Ontario. Image courtesy of Tim Hortons.

The city of Sudbury, Ontario, claims the honour of having installed the country’s first parking metres in August of 1940. Town bus on Queen Street West at Main Street, Brampton, Ont., c.1960. Region of Peel Archives/Cecil Chinn Fonds.

Blackburn’s Service Station in Vancouver, B.C., 1928. City of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4-: Bu.N274.2.

“In 1926, Dad bought a new Studebaker four-door with a canvas folding top. By the early 1930s, we had two tractors and it was time-consuming bringing the tractors in from the field for refuelling. A fuel truck was badly needed. The Studebaker was pulled out of the shed and into the workshop, where a complete motor overhaul was done. New tires were put on, the back half of the body was removed, a rear box installed that held four fuel drums. After harvesting, it was time to have some fun. The Studebaker was ideal for getting to a dance because we never ran out of fuel. Dad dubbed it the “Dancing Truck.” Antifreeze was a rare commodity in those days, so as it got colder we had to drain the water out of the radiator when not in use. After serving overseas in World War II and on my first visit back to the farm, I noticed the Dancing Truck was missing. My younger brother neglected to drain the rad during freeze-up and the resulting split in the engine block sealed its doom.”